Financial Wellness

How to boost diversity, equity and inclusion in pensions systems

As societies change and become more diverse, it is vital that pension systems also adapt. It is therefore important to understand the potential influences on people’s ability and willingness to save for retirement, if we are to uncover how pension systems can be more inclusive.

id

As societies change and become more diverse, it is vital that pension systems also adapt. It is therefore important to understand the potential influences on people’s ability and willingness to save for retirement, if we are to uncover how pension systems can be more inclusive.

Pension systems may sometimes fail to account for the diversity in modern societies. For instance, women usually have more limited access to pension plans than men. And new forms of work are emerging, producing new types of workers for whom pension systems may not be agile enough to cater.

It is also important to consider people’s attitudes and expectations towards saving and retirement, and how these can vary across socio-economic characteristics.

For instance, income, employment status, age, gender and ethnicity may influence how people perceive saving and risk-taking. These factors may also affect people’s confidence to make financial decisions, what they consider positive or negative about retirement, their attitudes towards planning for retirement and the financial commitments they expect to have.

Understanding these differences can shed light on how the design of pension systems could be improved to better serve under-covered populations.

So let’s look at some of the reasons why pensions systems are not fully inclusive, according to the OECD’s recent report – Diversity, equity, and inclusion in asset-backed pensions1. This report was supported by Standard Life and formed the latest phase of our thought leadership event programme, Thinking Forward.

Why pension systems are not fully inclusive

Several labour market factors affect people’s participation in pension plans. Across OECD countries, self-employed people tend to participate less than employees in pension plans.

For example, 60% of employees in Ireland are active members of a private pension plan, compared to 30% of self-employed workers. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, 74% of employees participate in a pension scheme, compared to 16% of self-employed workers.

Differences between these two types of worker can be greatly reduced in voluntary systems, when dedicated schemes are offered to each of them.

For example, in Belgium, distinct employment-related complementary pensions exist for employees and the self-employed. In 2021, 65% of Belgian employees and 56% of self-employed workers were active members of a complementary pension plan. So while a gap still exists, it is less than in many other countries.

Among employees, part-time and temporary workers tend to participate less than full-time permanent workers. Minimum thresholds on earnings, working hours and length of employment restrict access to occupational plans for part-time and temporary employees in many OECD countries.

The difference in participation between part-time and full-time workers is only 5% in Germany. But it reaches 29% in the United Kingdom, 36% in Ireland, and 44% in the United States.

In Germany, the small difference in participation rates across the number of working hours may be because regulation explicitly forbids discrimination between full-time and part-time employees.

Income levels also influence participation in pension plans. In the UK, Germany and the US, participation rates tend to increase initially with income, then plateau.

For example, in the United Kingdom, only 6% of people with a household income of less than £200 per week participate in a pension scheme. Participation then increases with income, but levels off at around 60% for people with a household income at or above £1,200 a week.

Demographic factors

Beyond labour market factors, participation rates also vary across demographic characteristics.

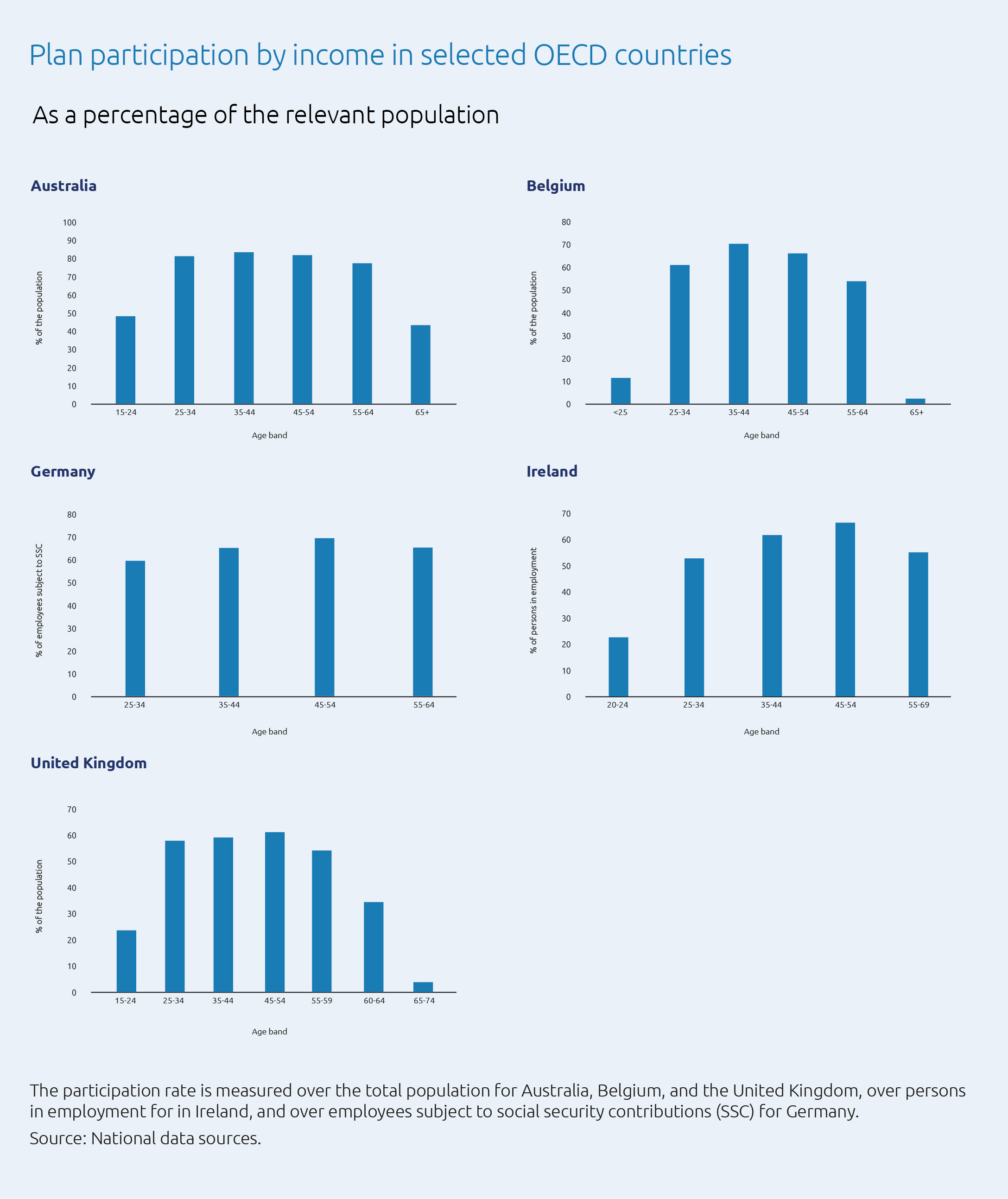

Within OECD countries as a whole, young workers tend to participate less in pension plans than other workers. For a selection of OECD countries – Australia, Belgium, Germany, Ireland and the United Kingdom – participation in pension plans peaks among middle-aged people and is lower for younger and older people.

Lower participation rates among people under-25 may be because many of them are still in education, and have no income to contribute to a pension plan.

This situation may still apply to some people aged 25–34. However, when measuring participation rates among employed people, instead of among the total population, younger workers still participate less in voluntary systems than older workers.

Figure 1. Plan participation increases with age in some OECD countries

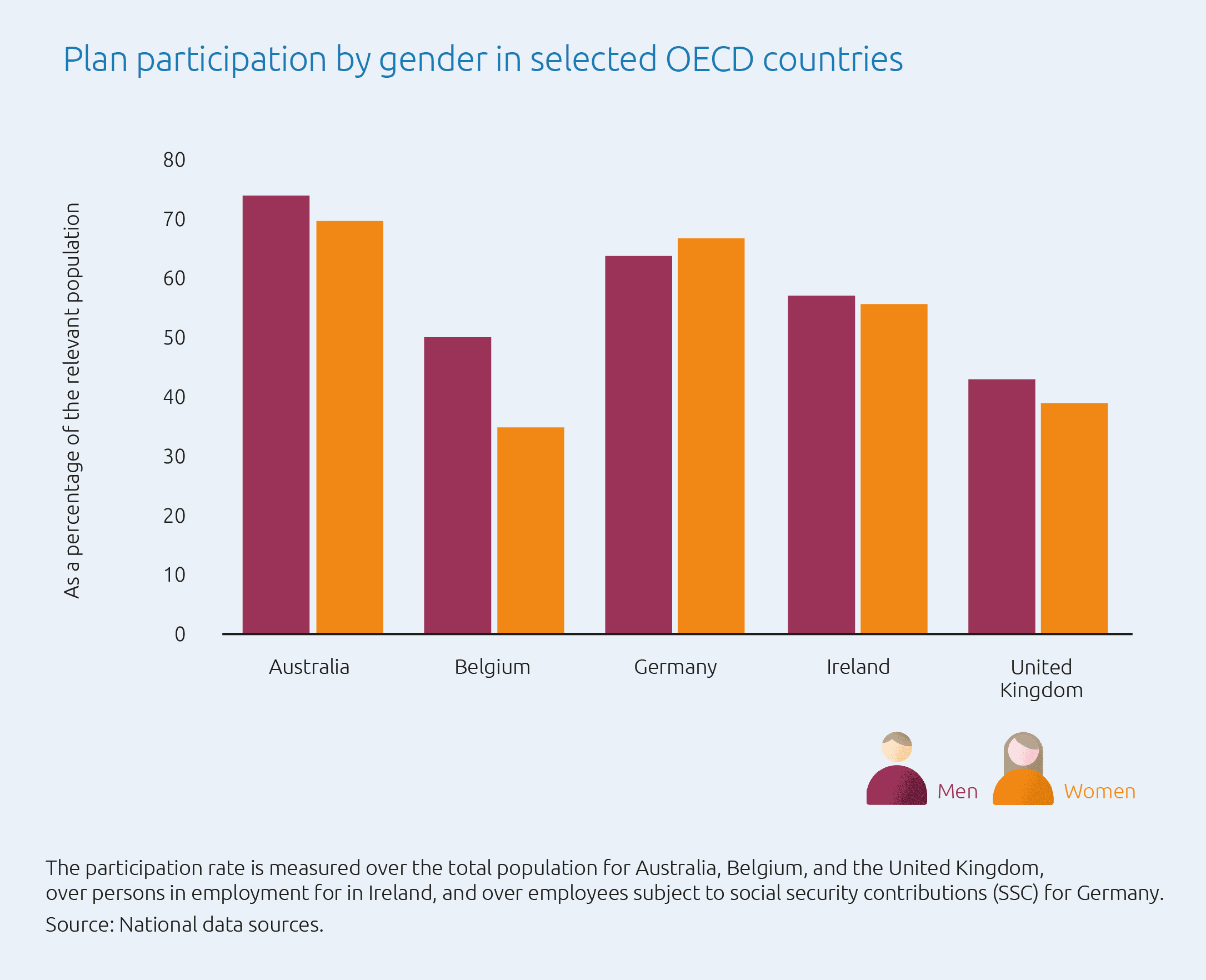

Women also tend to participate less in pension arrangements than men in most OECD countries. Germany is an exception. Here, women’s participation is high as they are over-represented in the public sector, where participation in occupational pension schemes is almost universal because of collective agreements.

Additionally, a larger proportion of women than men in Germany participate in voluntary Riesterpension plans among employees (34% versus 26%). The success of this arrangement among women may be because the government pays subsidies into these plans for members having children.

Figure 2. Germany is an exception when it comes to women’s pension participation

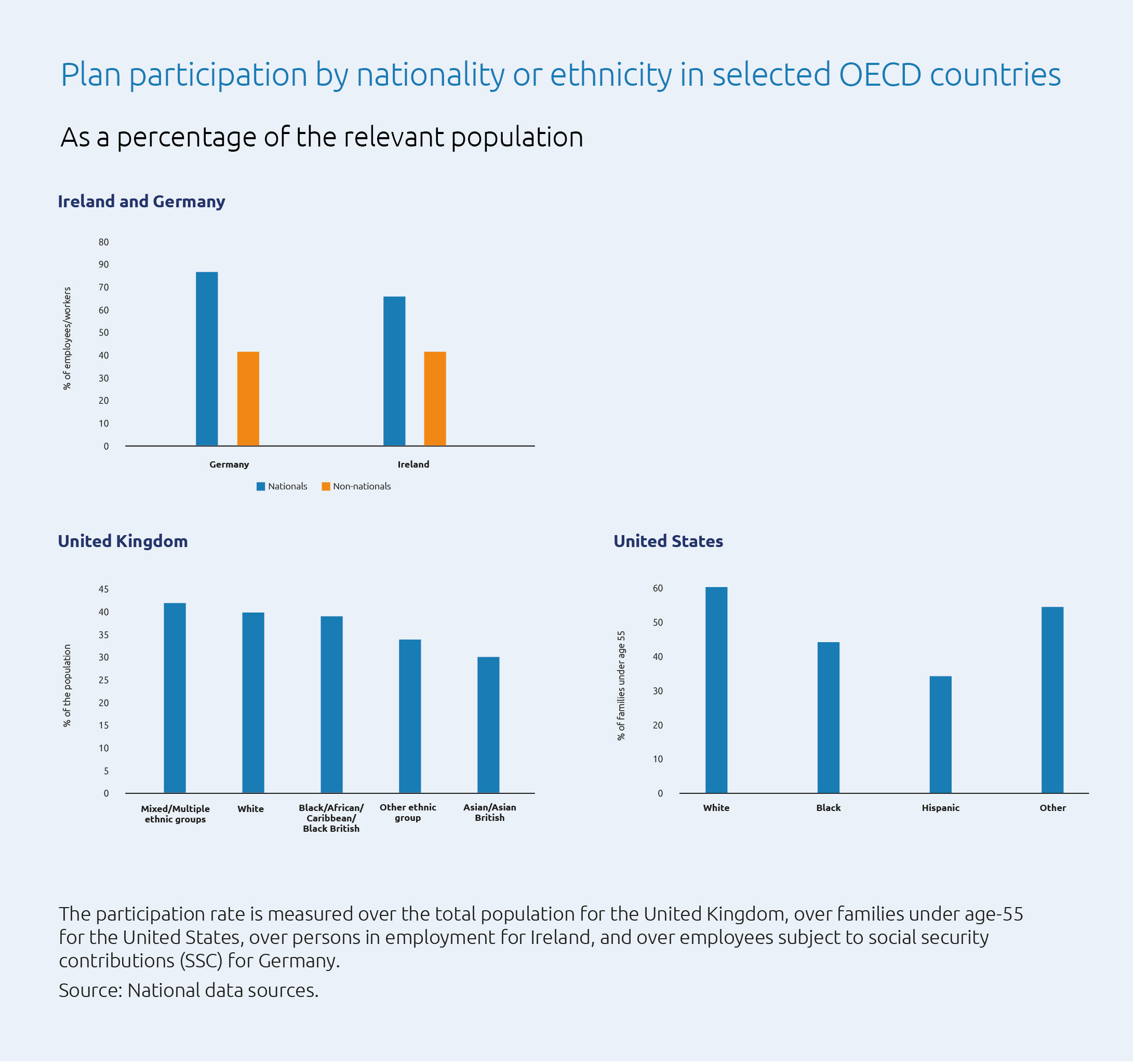

Non-nationals and people in minority ethnic groups may also participate less in pension plans than other people.

In both Germany and Ireland, non-nationals participate less than nationals. And in the United Kingdom, Asian people participate less than White people and those with a mixed ethnic background.

In the United States, people in Black and Hispanic families participate less in employer-sponsored retirement plans than those in White families.

Figure 3. Pension participation varies by nationality or ethnicity in many OECD countries

Making pension systems more inclusive

Behavioural biases and low levels of financial knowledge can affect people’s decisions relating to saving for retirement. In particular, present bias – the inclination to prefer a smaller present reward to a larger later reward – affects participation in voluntary systems, leading many people to postpone or avoid committing to save for retirement.

Many people also lack the knowledge to understand complex financial products such as pension plans. This may discourage some of them from enrolling in a plan even when they know it is ultimately in their best interest.

There are several possible policies to address these issues across many OECD countries, notably:

1. Introducing automatic or compulsory enrolment

2. Simplifying choice through automatic mechanisms and default options

3. Providing financial and non-financial incentives to join a plan

4. Providing financial education

Let’s look at each of these in more detail.

1. Automatic or compulsory enrolment

Automatic enrolment (AE) has positively affected participation in pension plans because it harnesses the power of inertia, while preserving individual choice with the opt-out option. However, AE’s impact on participation varies across countries due to different design features.

To increase significantly participation levels, the target population of the AE scheme should be broad-based. It might possibly cover all employees as well as the self-employed, and avoid eligibility criteria that excludes people who may benefit from building a complementary pension. Additionally, external incentives that may favour opting out need to be carefully identified and addressed.

2. Automatic mechanisms and defaults

For the typically less engaged automatically enrolled people, default options for the pension provider, the contribution rate and the investment strategy are essential. Yet these features need to be designed carefully to ensure that the income derived from the plan meaningfully contributes to retirement income adequacy.

Possibilities for doing this include fee caps and tender mechanisms to select providers, setting the default contribution rate at a low initial level and increasing it over time, and introducing a life-cycle investment strategy as a default.

3. Financial and non-financial incentives

Financial incentives help to promote retirement savings, though different people tend to react differently to different types of incentives.

Allowing people to deduct pension contributions from taxable income encourages middle-to-high income earners to participate in and contribute to pension plans.

Low-income earners, however, are less sensitive to tax incentives. This is because they may lack sufficient resources to afford contributions, may not have enough tax liability to enjoy tax reliefs fully, and are more likely to have a low level of understanding of tax-related issues.

Non-tax financial incentives – such as fixed nominal subsidies and matching contributions paid directly into the account of eligible people – are better tools to encourage retirement savings among low-income earners.

4. Financial education

Women’s specific needs should also be considered to ensure they participate in pension arrangements. Tailored financial education and communication could help to improve women’s financial literacy and knowledge of the pension system. This could help them to overcome their reluctance to deal with financial matters, and increase their confidence in using pension products and understanding of what action they could take given their situation.

In addition, allowing spousal contributions and providing subsidies for maternity and caretaking could help to counter the negative impact on retirement income for women who take part-time work or career break to perform care responsibilities.

Part-time and temporary employees, self-employed workers and informal workers also tend to have worse access to pension arrangements. This is because pension systems were designed initially to cater for full-time permanent employees.

As similarities exist between these workers and many women, some of the policy options to improve access to pension arrangements are the same for non-standard workers and women.

In particular, regulation should ensure non-discriminatory access to pension plans by avoiding the use of criteria based on salary, working hours, length of employment and type of contract, including for AE schemes.

Australia recently removed the AU$450 monthly income threshold to expand the coverage of its mandatory pension system. This measure came into effect on 1 July 2022. The Retirement Income Review estimated that around 300,000 more people would receive pension contributions, 63% of whom are women.

Moreover, flexibility in the level and timing of contributions could help workers with volatile earnings and career breaks to contribute more when their situation allows.

Given that many of these workers tend to have low earnings, framing contributions in small, frequent amounts may increase the feeling of affordability. Non-tax financial incentives, such as government subsidies and matching contributions, could also be introduced to encourage enrolment and contributions.

Self-employed

For the self-employed, specific policies may be required to make saving for retirement better tailored to their needs. In particular, they may value pension plans designed specifically for them and allowing, for instance, to earmark part of their business profits or sale proceeds for retirement.

They also view positively hybrid products combining short-term, liquid savings with retirement savings. Additionally, as introducing AE is not as straightforward for them as for employees, automatic savings could be facilitated by using the digital services and platforms that self-employed workers use to run their businesses.

Ultimately, retirement savings systems need to be more inclusive and responsive to the diverse capabilities and needs of different demographic groups. A one-size-fits-all approach to engagement will not succeed.

Instead, engagement activities need to be tailored and policy solutions improved so that everyone can achieve retirement security.

Read the full OECD report: Diversity, equity and inclusion in asset-backed pensions

Find out more about our Thinking Forward programme: Thinking forward | Standard Life

1These views do not necessarily reflect those of Standard Life.