Saving and Investing

What the UK’s economic challenges mean for long-term savings and consumer behaviour

Paul Johnson CBE, Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, discusses the UK’s economic challenges and how this may affect people’s retirement plans.

id

We spoke to Paul Johnson CBE, Director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, about the UK’s economic challenges and how these may affect people’s retirement plans.

Many people are facing increased financial pressures and vulnerability due to the UK’s current economic challenges.

It’s therefore vital that employers and pension providers understand the likely impact of the UK’s economic constraints on people’s pensions, retirement plans and broader financial behaviours.

To do this, we spoke to one of the UK’s leading economists, Paul Johnson. This formed the latest phase of our thought leadership programme, Thinking Forward .

Below is a summary of Johnson’s thoughts on the range of topics discussed.

Things have got harder

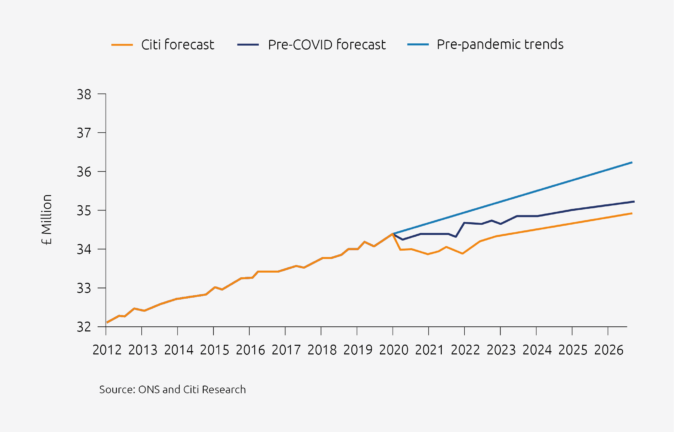

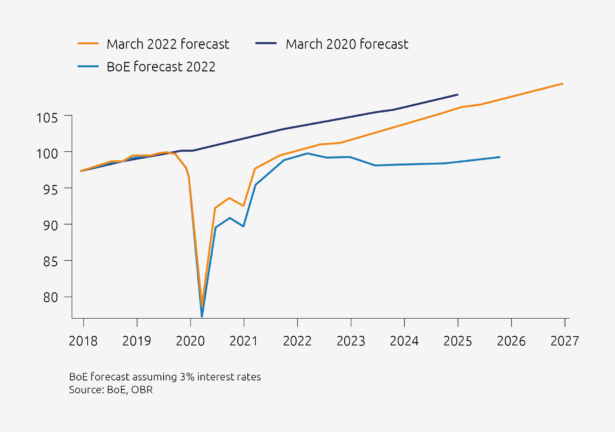

Since the mini-budget in September, the UK’s economic situation has worsened considerably, noted Johnson (see Figure 1).

“The Bank of England [BoE] projects that the economy will be smaller in 2026 than in 2020. It’s extraordinary that we may see six years of no growth. This is projected to create enormous problems in terms of spending cuts and tax rises.

“This is actually the Bank of England’s more positive forecast, though some parties might argue it is unduly gloomy.”

Figure 1: The UK’s economic outlook has worsened since March 2022

Global confidence in the UK economy has plummeted since September – driven partly by policy and lack of confidence in the UK’s stability, said Johnson. Going forward, many of the government’s policies will be driven by its desire to shake off the so-call “moron premium”, which has been imposed on the UK by the international markets since the mini-budget.

“The new prime minister and chancellor have already helped to reduce the turbulence,” said Johnson.

However, Johnson said it is unclear when we will return to the relative normality of six months ago. “The financial markets are still looking at the UK more vigilantly than either Germany or France.”

Lagging behind rest of G7

The UK is the only G7 country not to have returned to its pre-pandemic economic levels. Brexit and political and economic uncertainty have clearly played a role, said Johnson.

“Going forward, the big question for the government is how tough it should be – in terms of its spending cuts and tax rises – how soon should it be tough, and for how long should it delay some painful measures.”

Inflation rising, household income falling

Inflation is forecast to come down relatively quickly in 2023. Contrary to some mainstream commentary, Johnson said that energy price volatility was only about a third of the reason for the UK’s inflation problem.

“About two-thirds of the inflation is nothing to do with Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Government expenditure and monetary loosening around the world during Covid-19, alongside broader supply side problems, were certainly large factors.

“We have a disequilibrium, where we face tight supply, but high demand. We need to ensure supply side constraints don’t get any worse.”

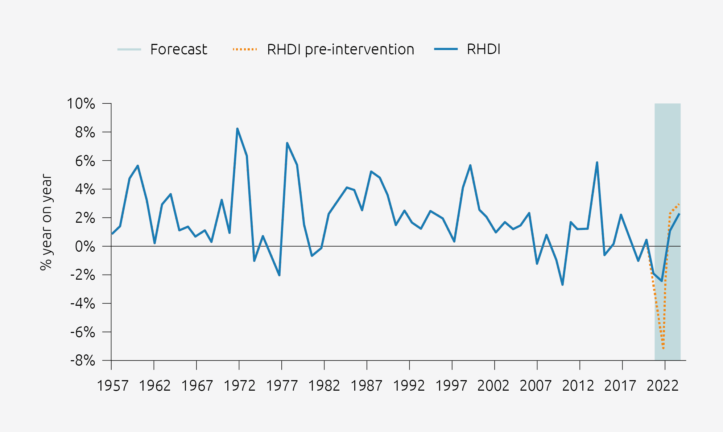

The UK is facing a historically big hit to household income (see Figure 2). This year was among the three worst years for average household income in the last 70 – and would have been even worse without intervention on energy.

“Average earnings haven’t grown over the last 15 years,” said Johnson. “This is the worst stretch for 200 years by some measurements. The financial crisis of 2008–09, on the other hand, came off the back of 30 years of income growth.”

There is one positive, however, noted Johnson, which is that during the pandemic there was a big increase in savings among a fairly large proportion of the population.

Figure 2: Household incomes face a historically big hit

(RHDI: real household disposable income)

More broadly, many people in their 20s and 30s are probably worse off than their parents, said Johnson. “People in their 30s in middle of the earning distribution are more likely to be renting. This large-scale move towards more people renting has probably been one of the big political and economic change of the last 15 years.”

There is also an uptick in people aged 50-plus renting, noted Johnson. “At some point in the future, up to a quarter of all retirees could be renting.”

Economic inactivity

The rise in economic inactivity has reduced the size of the UK labour force. This rise is principally from the loss of people in their mid-fifties and above from the labour force. Arguably this is one of the big socioeconomic challenges to be tackled.

“The current levels of economic inactivity are extraordinary,” said Johnson. “The number of vacancies relative to the number of unemployed is very high.

“It’s one of the biggest and most important unknowns to me, and mostly doesn’t seem to be down to ill health.”

A group discussion ensued as to whether this trend was mostly due to voluntary retirement, and whether this was a one-off blip, or an ongoing trend.

It is possible that this trend might be somewhat reversed, with more people unretiring due to the cost-of-living crisis. In any case, rising economic inactivity has big implications for the economy – in terms on strain on welfare, tax receipts, as well as on the pensions industry.

Figure 3: Rise in economic inactivity has reduced size of labour force

Standard Life research indicates that many people are chasing extra income in light of the cost-of-living crisis. So, in light of rising economic inactivity, to what extent should the government and employers do more to encourage more people to return to work?

(Learn more here on What is Driving the Great Retirement? . This research is produced by Phoenix Insights, the think tank of Phoenix Group, the parent company of Standard Life.)

In many respects the UK is going through a “very strange recession”, said Johnson. “It doesn’t feel like a recession in terms of the labour market, which is very tight. We have fewer people in the labour market than compared to pre-Covid. In this respect the UK’s situation seems to be virtually unique within the G7.”

In general, the UK is seeing quite an “even” recession, with widespread small-scale reductions in income, rather than mass unemployment (though high recent redundancies have been seen in some sectors, such as tech).

Going forward, really high levels of unemployment seem unlikely, said Johnson. “The BoE forecasts higher unemployment, but this would leave us with still relatively low levels of unemployment – back to levels of five or so years ago.”

Another trend Johnson identified was that for first time since the financial crash, earnings have really started to take off for the top 1% of earners in the last 12 months or so (largely in the financial services).

Tax burden

The UK tax burden is set to stabilise at a historically high level – certainly the highest since immediately after the Second World War, though still relatively low compared to other western European countries.

Corporation tax will be at highest level in history in the next few years, noted Johnson. “It is hard to see how this trend is revered when the government faces the requirement to spend more on the NHS, pensions etc, while being unable to spend much less on other areas.”

One thing for this government to worry about is public sector pay, the practical impossibility of giving inflation-lined pay rises, and the response of public sector workers, said Johnson. “Public sector pay has gone down in the last decade, with teachers and nurses around 10–15% worse off than in 2010.”

Future of the State Pension

As a fraction of national GDP, the State Pension is not increasing substantially over time, said Johnson. “Over the next 30 years, it is not the State Pension that will drive up government expenditure, so much as national health service and social care.

“The State Pension is not especially generous by international standards. That said, at some point we have to move away from the triple lock. What we really need is a view as to what level it should eventually settle at.”

International comparisons

So what have other countries been doing to manage the economic headwinds, and why does the UK appear to be doing worse?

In Johnson’s opinion there are two main macro-economic reasons why the UK has recently fared worse than many similar countries: 1) Brexit, and 2) political and economic stability.

“Putting up barriers with the UK’s largest trading partner has clearly played a part. And more generally, the UK has experienced a relative lack of political and economic stability in recent years, along with an undermining of many of its traditional institutions. This is genuinely costly. Big businesses need confidence in the stability and openness of the countries in which they invest.”

Of course, a big unknown facing the UK is which party will occupy government following the next general election, which is expected to take place in late 2024 or January 2025.

If the Labour Party wins the next general election, it won’t have that many economic and spending options, said Johnson.

“The economic mess won’t have been cleaned up – unlike when Labour came into power in 1997. If Labour wants significantly higher spending, it will need to raise taxes even further.”

From a broader international perspective, David Harris, Managing Director of TOR Financial Consulting, said three main trends are being seen:

- Governments are focused on fighting inflation.

- Pension reform has slowed down as other economic and social matters are prioritised.

- Previous ambitions to increase pension contributions – among employees and /or employers – have been stifled, as individuals and businesses face other pressing financial challenges. This may slow down work to reduce the gender pension gap and the disadvantages faced by some other social groups.

“Some countries are considering pausing pension contribution compulsion,” added Harris. “For example, Australia was due to push up compulsion from 10.5% to 12%, but will a lengthier pause now take place?

“On the other hand, Ireland is forging ahead with its introduction of AE – which is brave. With respect to pension reform right now, it’s vital to get the messaging right – we see in New Zealand that KiwiSaver (their AE model) is stuck with low contribution levels (employee and employer) and sharp withdrawal increases for housing purchases.”

Changing attitudes

Amid the current economic turbulence, how have public attitudes perhaps been affected by the pandemic, among other recent events?

One attendee wondered whether government expenditure during the pandemic (through the furlough scheme), might have altered some public attitudes towards debt and management of the national finances.

“In some quarters, there’s a deep well of opinion that financially the government can do whatever it wants,” agreed Johnson. “But the response to the September mini-budget showed this is absolutely not the case.

“If the Labour Party wins the next general election, it may well be criticised by the hard-left over the economic constraints it will probably have to introduce. This will not be dissimilar from how the Tories will be criticised from the hard-right for raising taxes.

“Political moderates in both the main parties will therefore have to stay strong in the face of populism, from both the political left and right.”

To wrap up, Johnson was asked whether he had any final advice for employers?

He suggested that more could be done to address the challenges faced by women who transition to part-time work – particularly with respect to pay and opportunities for promotion.

“Some employers can still do more to treat women who are mothers and/or who work part-time better, in terms of pay and promotion.”

The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of Standard Life.