How do other countries help people in their 50s and 60s return to work?

This article summarises findings from the new report ‘The role of active labour market programmes in supporting the over 50s: UK and international evidence’ by Philip Taylor, Beate Baldauf and Eamonn Davern and published by the Warwick Institute for Employment Research. The research was commissioned by the Standard Life Centre for the Future of Retirement and published in December 2025.

Good work is important for people’s day-to-day finances, long-term savings and wellbeing. As a result, extending working lives is one of our priorities at the Standard Life Centre for the Future of Retirement. Since many other high-income countries also have ageing populations, we are interested in what the UK can learn from international examples of supporting longer working lives.

We commissioned the Warwick Institute for Employment Research, and their new report focuses on employment support programmes which support people aged 50+ to return to work, especially those disadvantaged in the labour market, for example people who are long-term unemployed or disabled. This article summarises the findings from the research, and you can download the full report from the Institute’s website.

Why employment support for over 50s matters

The topic of longer working lives is by no means new, but it has received renewed attention recently. In December 2025, the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee featured labour market participation as a central issue in its report ‘Preparing for an ageing society’, and made a recommendation that “the government should set out the policies it has in place to encourage those in their mid-50s to mid-60s to return to or remain in work”. Similarly, the Keep Britain Working Review, led by Sir Charlie Mayfield, highlighted “longer, healthier working lives for older workers” as an important issue. Last year, longer working lives also featured in reports published by the OECD, the IMF and Goldman Sachs.

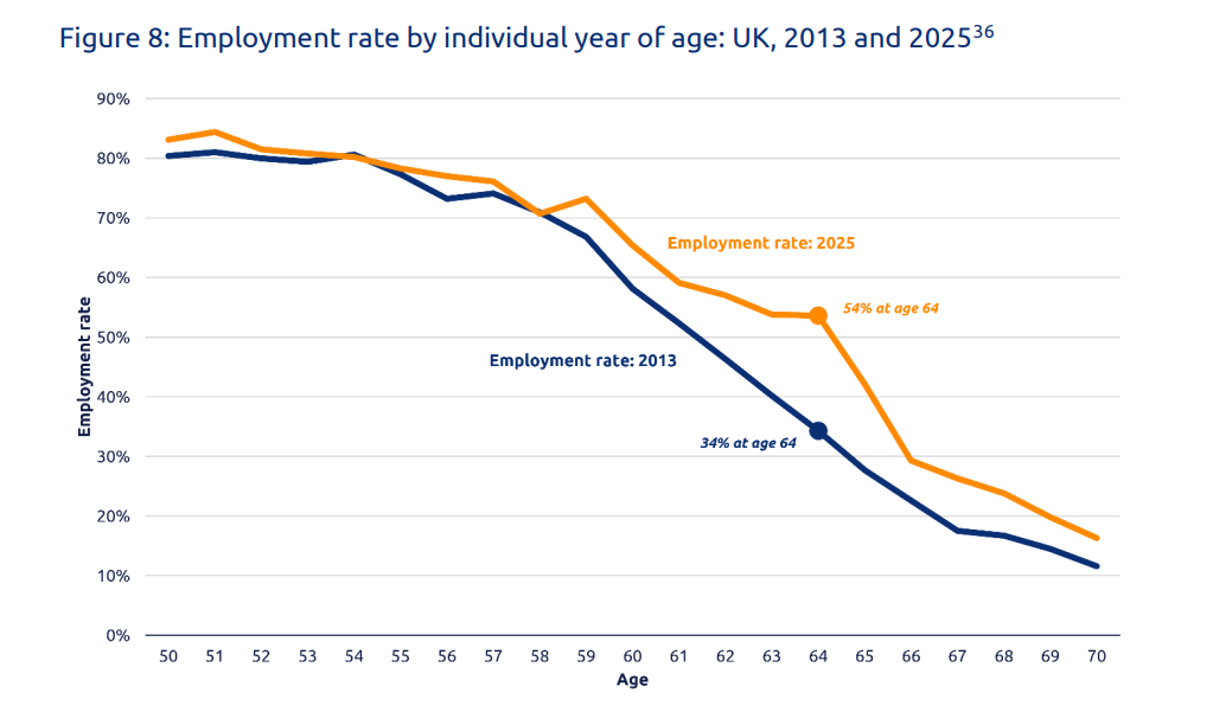

The positive side of the story is that longer working lives are already here. In the UK, people retire five years later today than they did 30 years ago. At the age of 64 over half of people are in paid employment, up from only one in three in 2013.

Source: Jam tomorrow? Work, finances and retirement in an era of a rising State Pension age

For most people in their 50s and 60s, being in work matters for their long-term financial security, providing higher income from earnings and enabling them to build up private pension savings, thereby helping them to be prepared for retirement.

Researchers have also found that, on average, just one day of work a week improves people’s mental health and wellbeing. There is even some evidence that working in your 60s can be good for your health, depending on the type of job you do.

However, it remains the case that people in their 50s and 60s are less likely to be in work than younger age groups. While many are entering retirement through choice, others leave work earlier than they would choose, for example due to ill health, unpaid caring responsibilities, redundancy or other reasons.

Losing a job or leaving work can be difficult for people aged 50+, who are more likely to spend six months or more unemployed, and on average face a larger pay cut when they do return to work, in comparison to younger age groups. Over 50s who are out of work may face a range of barriers to returning, including both personal circumstances (such as ill health or caring responsibilities) and wider factors in the labour market (such as a lack of good quality part-time jobs or age bias in recruitment processes).

In this context, careers advice and employment support can make a significant positive difference. However, we also know that employment support programmes tend to have worse outcomes for people in their 50s and 60s, compared to younger cohorts. So how do other countries support longer working lives?

Extending working lives is an area of policy focus in many countries, not just the UK

In terms of employment among people in their 50s and 60s, the UK is in the middle of the pack among high-income countries. The UK has an employment rate of around 66% among people aged 55-64, higher than both the United States and France, but lower than other countries including Japan, Sweden, New Zealand, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland. This international comparison suggests there is scope to increase employment among over 50s in the UK.

The new report describes policy changes different countries have made over the last few decades with the aim of extending working lives. Japan now requires employers to offer employment opportunities for workers up to the age of 65, whereas previously many people retired at 60. In Sweden, reforms to the pensions system first implemented in the 2000s increased the financial incentives for people to continue working in their 60s. Some countries, including the UK, have raised their state pension age, which encourages people to work for longer as well as reducing the fiscal cost of pensions. For example, the Netherlands and Denmark have both increased their state pension age from 65 to 67.

According to a report from Eurofound, across EU member states, the employment rate for workers aged 55-64 increased by almost 20 percentage points between 2010 and 2023. This is a helpful reminder that the UK is far from alone in seeking to extend working lives, and having some success in achieving this in the last 10-20 years.

Active labour market programmes for over 50s in other countries

With a few exceptions, such as 50Plus Champions in Jobcentres, the UK currently has very few employment support programmes – also known as ‘active labour market programmes’ – specifically aimed at over 50s. However, there are interesting examples of age-specific initiatives in other countries.

In Switzerland, a programme called Supported employment for over 50s consists of six-month individualised job search support for long-term unemployed people aged 50+, with continued support available after someone starts a job. As of the end of 2024, of the 1500 participants taking part in the programme, 51% found a regular job within six months.

In Germany, a programme called Perspektive 50plus supported long-term unemployed people aged 50+, and ran in three phases from 2005 to 2015. Through the programme, German Jobcentre staff supported jobseekers with personalised support, partnered with employers, and sometimes provided wage subsidies. One study concluded that Perspektive 50plus was “more innovative and cost efficient” than other programmes. Another study suggested there may have been a 5-10 percentage points increase in unsubsidised employment as a result of the programme.

Workforce Singapore, a government agency, offers careers advice and employment support to Singaporeans aged 50+ through the ‘Employment Support for Seniors’ programme. To complement this, the Ministry of Manpower offers grants of S$2,500 per worker aged 60+ to employers who provide part-time re-employment opportunities. As a condition of the grant, employers are required to adopt Age-Friendly Workplace Practices, and offer flexible work arrangements and structured career planning to workers.

Despite these examples, however, the report notes that the number of age-specific programmes and initiatives is limited. Some countries have closed previous 50+ programmes, even though age-neutral programmes may fail to address this age group’s specific needs.

What does effective support to help over 50s return to work look like?

The report includes many examples of active labour market programmes, but there are few systematic evaluations, and it is not straightforward to make comparisons between different countries. Nonetheless, the research does enable us to identify some common themes in successful programmes.

First, tailored and person-centred support is a consistent theme. For example, the six months of tailored support from a coach was identified as a success factor in the programme in Switzerland. Likewise, in the programme in Germany, “individualised, and especially more frequent and intensive, counselling was also identified as a factor in delivering more employment outcomes than the mainstream approach.” There is a wide range of evidence which suggests that personalised support is particularly important for people facing barriers to returning to work: Individual Placement and Support (IPS) is a well-known example currently active in the UK.

Second, employer engagement is an important theme. ‘Employer engagement’ can cover a wide range of activities, ranging from working with employers on recruitment or workplace adjustments, organising career fairs, or providing wage subsidies. Programmes in Austria and Germany both offered wage subsidies to employers for employing long-term unemployed people aged 50+, while in Germany employers were also offered advice about age-friendly employment practices.

The report found the evidence on the effectiveness of wage subsidies specifically is mixed, but does conclude that employer engagement – however this is achieved – is important. A lack of employer engagement is sometimes a weakness in active labour market programmes in the UK.

More positively, over 500 UK organisations have signed the Centre for Ageing Better’s Age-friendly Employer Pledge, and ongoing government reforms aim to transform Jobcentres into a Jobs and Careers Service which engages employers more effectively. The report also highlights a positive UK example of employer engagement: Sector-based Work Academy Programmes (SWAPs). These are short programmes lasting around six weeks, aimed at people who are unemployed, and consist of pre-employment training, work experience and a guaranteed interview. They are run as a partnership between Jobcentres and employers. An evaluation found that the impact of taking part in a SWAP was higher for the 50+ age group than for younger age groups: an additional 15% of the 50+ age group were in employment two years later as a result of participating in a SWAP. The partnership with employers involved in SWAPs is likely an important factor in their success.

Third, the report also finds evidence that training/learning can have a positive impact on people’s likelihood of being in employment. For example, one meta-evaluation concluded that training increases the probability of unemployed people aged 50+ finding a job. Another meta-analysis concluded that training programmes increase employment (for all ages), but that this positive effect takes 2-3 years to appear after completion of the programme.

Last year, our research with the Learning and Work Institute found a causal link between learning/training and employment. After two years, 4% more of the adults who accessed learning or training were in work, compared to those who did not. These findings are particularly relevant as adult skills policy is moved from DfE to DWP, with the potential for strengthening integration between careers advice, employment support and adult training/learning.

The report also includes examples of ways to promote interest in learning/training in mid or late career. For example, in Singapore, the ‘SkillsFuture Mid-Career Training Allowance’ offers grants to people aged 40+ to pay for accredited types of training/learning. Here in the UK, the Lifelong Learning Entitlement will launch in September 2026, offering loans to cover tuition fees for qualifications at levels 4-6 for anyone aged between 18 and 60 – although there are persistent worries that this policy will suffer from low take-up, as we explored in previous research.

Conclusion

The new report provides a wide range of international evidence from which we can learn. Here in the UK, there have been a number of pilots designed to support over 50s return to work, such as Support to Succeed in Greater Manchester, and the Centre for Ageing Better has summarised some of the lessons for policy makers and commissioners. Since people aged 50+ may find it harder to return to work, there is a strong case for renewed attention on better supporting people in this age group. We think this means improving and expanding careers advice and employment support, including via 50+ specialists within the new Jobs and Careers Service. Combined and Strategic Authorities should also consider how their commissioned employment and skills programmes are tailored for people aged 50+. This new research report is full of useful ideas and evidence from other countries about how to make sure these programmes are effective in helping people return to work and improve their long-term financial security.